Motivation

As an engineer it is my second nature to understand how things work. Being a database and systems engineer enthusiast, I always wondered how databases work! Why not dump everything into a text file? As I delved deeper into understanding how databases work under the hood, I realised databases are much more than a simple data dump.

So I went ahead and implemented a simple key-value database in Go which uses WAL(write ahead logs) for persistence. Well, the best way to learn something is by doing it.

What is a WAL?

A WAL or a write-ahead log is a one of the simplest techniques databases use to guarantee durability. The ideology is very simple: before making any changes, append what you are doing into a file.

This in some way can also provide persistence. If you know the series of events that occurred, you can always rebuild the database back to its original state.

Think of it like a diary for the database:

-

Every time I perform something, I write it at the end of the diary.

-

If I forget an event I can always revisit the past through the diary to remember it again.

Many databases like Postgres, Redis, RocksDB use WAL as a means to achieve durability. In my project, I swapped out its role for durability with persistence. Of course this is not the best way to do it, but is a good starting point to learn about databases.

Designing the Key-Value Database

Before we get to the design of the Key-Value database let’s discuss what a key-value store or a KV database is.

A key-value database is a database paradigm where data is stored in pairs. The pair being the Key; represents a label for the data, and the Value; represents the actual data.

Commercially available databases use a HashMap as a data-structure to maintain the relationship between the two pairs. Persistence is achieved through other data-structures which will be stored on the disk.

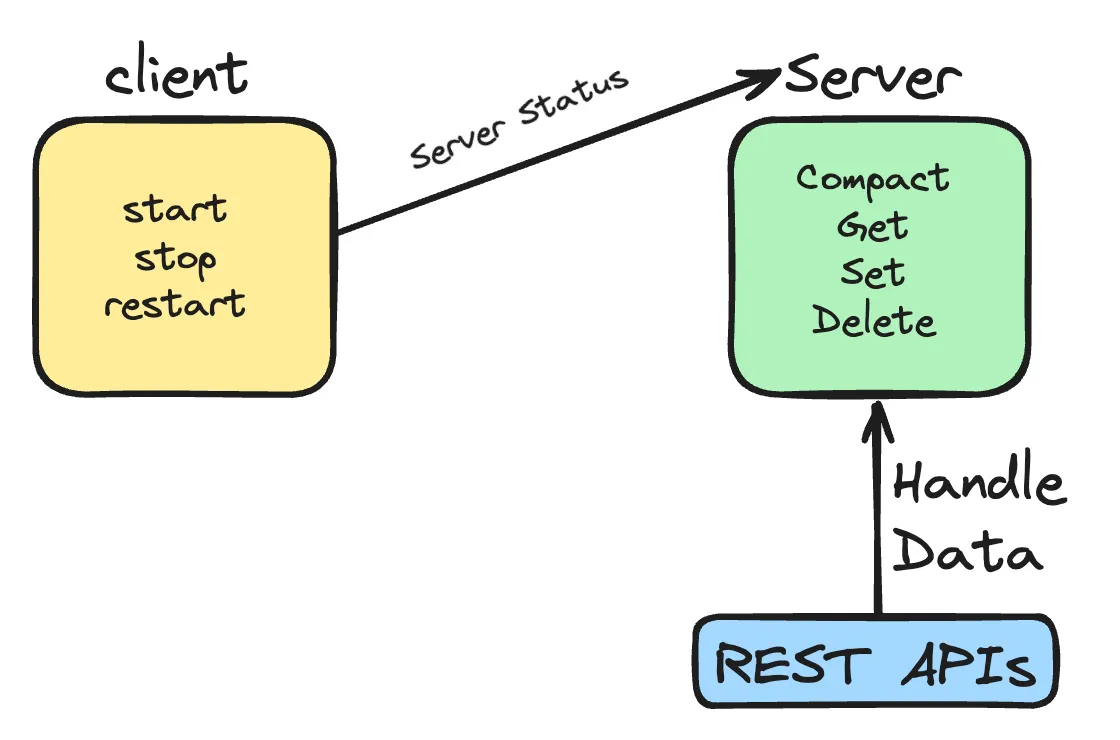

Now, let us have a look at the design of my Key-Value data-store. The database is split into 2 main parts:

- Client: The CLI tool which deals with starting and stopping the database server.

- Server: The server which actually performs the database operations.

Server is where the crux of the application resides, so let us dive deeper into that.

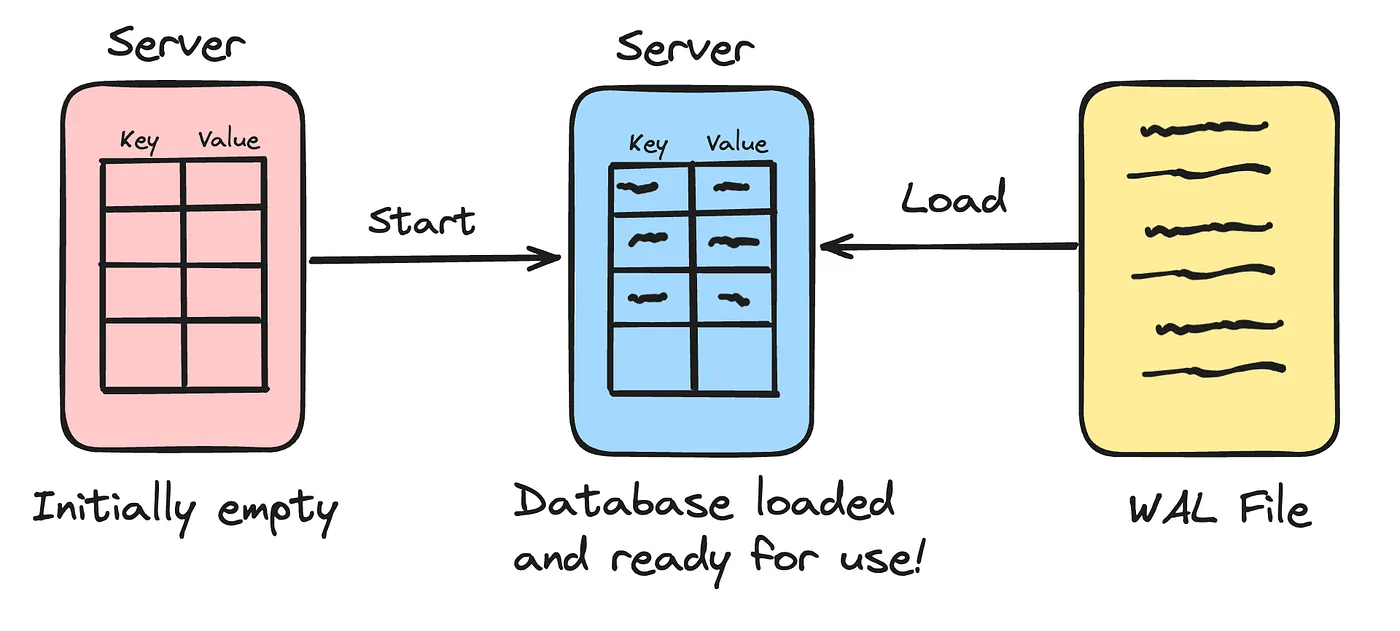

- In-Memory Hash Map: The database uses an In-Memory HashMap to store data during run-time. Since the data is loaded into memory, retrieving of data is extremely efficient and pretty much instantaneous.

- Write-Ahead Log File: Sure the HashMap stores the data during run time, but what to do if the server crashes? All the data will be lost. Here comes the WAL file. The WAL file stores all the operations performed on the database. Hence using this file we can rebuild the Hash Map in case an application failure occurs.

- The Recovery Phase: This is the phase where the data is brought back into the system memory. If the server ever goes down for some reason and the in-memory data is lost, we can restart the server to bring all the data back into the server on start-up. The server basically walks back in time to reconstruct the database.

This gives you an overall architectural view of the database. In the next section, I will be explaining a bit more on the implementation details, so be ready for a short but insightful technical overview.

Implementation

For this implementation I have decided to use Go as the preferred programming language due to its speed, rich ecosystem and simplicity.

Logging Details

Each log entry is defined using a struct to make it an atomic data type:

type LogEntry struct {

Operation string

Key string

Value string

}

Where the operation can be: “SET” or “DEL”.

Whenever a user makes a request to add a new entry to the database or delete an entry from database, a log is written to the log file with structure mentioned above. Example:

- Adding an entry: SET “hello”, “world”

- Deleting an entry: DEL “hello”

We have also defined a variable which uses the in-built HashMap which Go provides:

type KVStore struct {

Store map[string]string

}

This struct will help accessing the in-memory elements.

There is also a component in the codebase which deals with appending the entries to a file. The issue would be storing these entries in a way that it maintains separation, to do that we need to serialize the entries into bytes and add it to the file. This ensures that each line corresponds to one of the entry and hence can easily be extracted when needed.

Handling Compaction

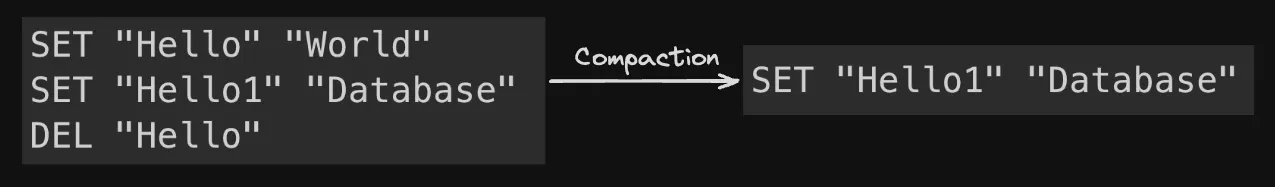

So far it looks good! But there is one issue, as the log file gets larger it becomes harder to parse the file. Imagine the time it would take to parse a log file which has 1 million entries! This is not ideal.

Here is where a concept called compaction comes in. Compaction as the word suggests is the process of reducing the size of the log file.

Now, another thought experiment! Can we just remove logs to reduce the size? NO! We cannot do this as it would lead to loss of data, but what we can do is remove the logs which are redundant, for example:

-

Let’s say I added an entry (“Hello”, “World”), this gets added to the log file as “SET Hello World”. Immediately after that I add another entry (“Hello”, “Database”), this would also create an entry into the log file which is seen as: “SET Hello Database”. The value for hello as changed from World to Database, the old log entry does not have value anymore as only the latest entry will be useful for recreating the database. Therefore we can delete the first entry and reduce the size of the file.

-

Similarly once you delete an entry from a database using: "DEL Hello", the older logs which deal with the key Hello are not necessary anymore as it should not exist in the new database. Therefore we can remove any old entry in the log file which deals with the deleted key hence saving more space.

Recovering Data

Now that we’ve solved the problem of WAL growth with compaction, let’s revisit the recovery process.

When the server starts up, it needs to rebuild the in-memory hash map from whatever is stored in the WAL file. Since each log entry is stored on a new line in a serialized format, the recovery process is simply:

- Read the log file line by line.

- If the operation is SET, add it to the in-memory hashmap.

- If the operation is DEL, remove it from the in-memory hashmap.

- Go through the whole file.

Following these simple steps, the database will be fully recovered to its original state before the server crashed.

Short-Comings of KV WAL Database

While this concept works as a minimal key-value database, there are still some important challenges that show up when used in practice:

Recovery Time

Imagine there are a million entries, it would take a lot of time to perform the recovery step. Now some of you might point to the compaction process that I implemented, but that too has its limitations. Compaction would be useful if there are any redundant entries, but what if all the entries are unique? We cannot delete entries randomly and lose critical data.

Though there are ways to solve this issue, but it would be better to go with a different way to achieve persistence. Generally databases use, B+ trees or LSM trees to achieve persistence (more on these in a later blog… maybe?).

Memory Explosion

Now back to the 1 million keys scenario, if there are a million unique keys and we want to store them in-memory, it would cause your RAM to be used extensively and eventually run out space. To solve this we could make the in-memory data structure work like a cache and load the entries dynamically but since the WAL is an append only file, there is no way to find entries fast.

Compaction Frequency

When and how often to compact the database also poses to be challenging task. Compacting the file too often would cause unnecessary load on your system and compacting too rarely makes the start-up extremely slow.

Each application has a different use case and hence it is better to set the compaction criteria dynamically which is a tricky task to do.

Future Improvements

Some interesting steps that can be taken to make this project more usable would be:

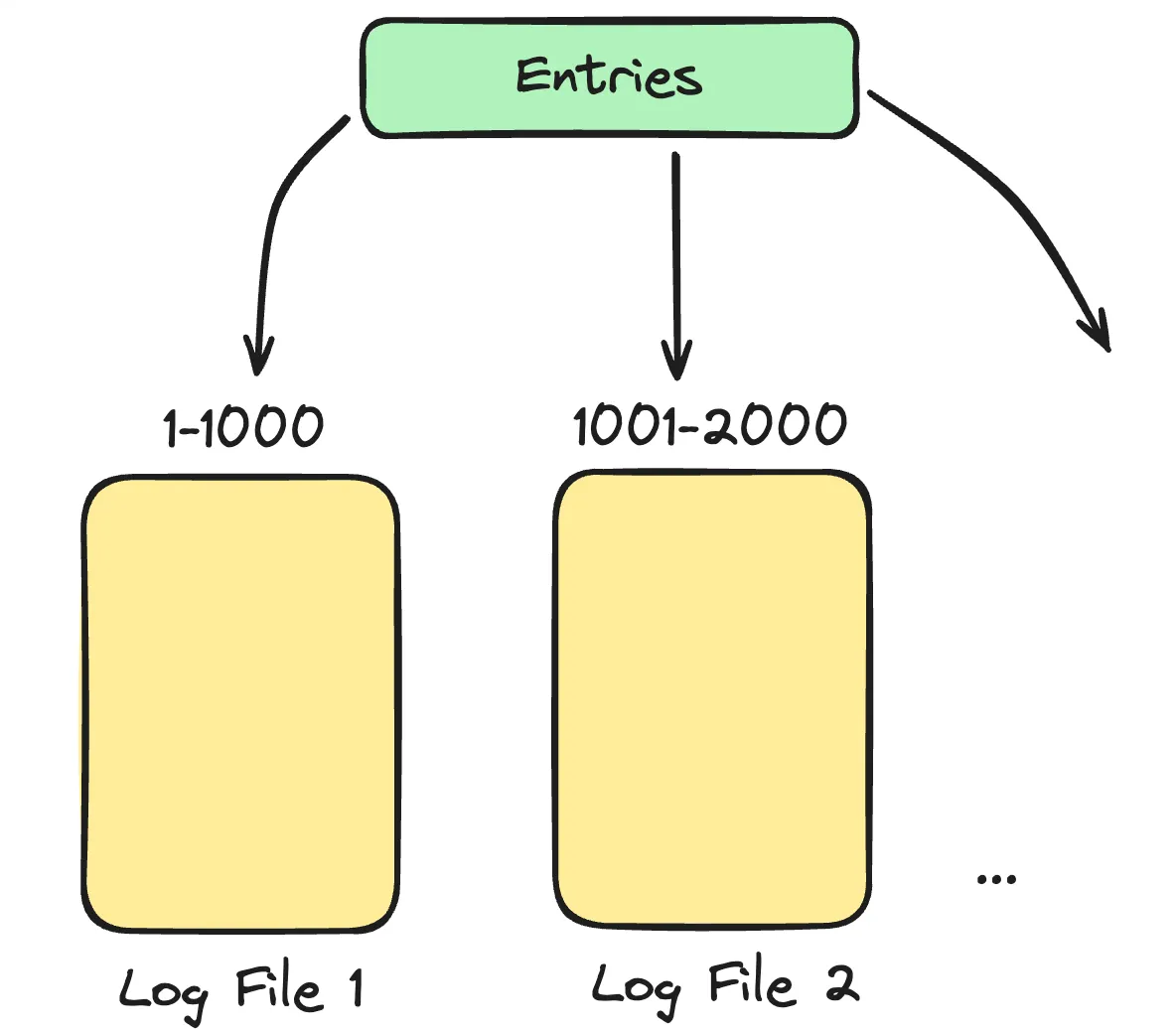

-

Range based partitioning: To deal with large recovery times, we could split the log files based on the range. For example, all keys between 1 and 1000 can go to file1, 1001 to 2000 can go to file2 and so on. While recovering all these files could be read in parallel and hence making it faster.

-

Checksums: Add some integrity checks to the entries so that the integrity of the entries can be verified. Let’s say the server crashed while a log was being written, due to this the log was written halfway. Adding a checksum can help with identifying such errors than can happen while using the database.

-

Snapshots: Periodically dump the HashMap values to the disk using other data structures which are faster. In this case we could use the WAL for what it was intended to be used for, durability.

Conclusion

Building this key-value store was a fun way to peek under the hood of how databases function. It started with a simple hash map and then evolved into something persistent using a write-ahead log.

Of course production-grade databases like Postgres, Redis and RocksDB go far beyond this, but the core ideas are the same. By working through this project, I now better appreciate the careful engineering trade-offs databases make between performance, durability and complexity.

If you’d like to play around with my implementation, the source code is available here: link. Feel free to break it or contribute your ideas to the codebase!